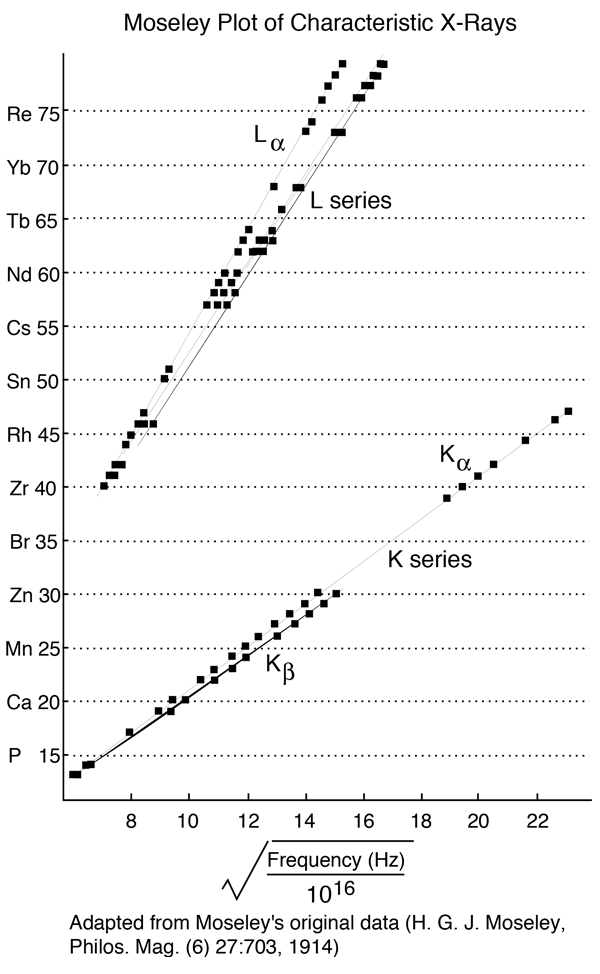

Moseley's Modeling of X-ray Frequencies

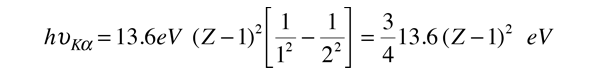

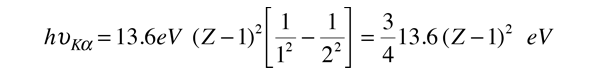

Moseley's empirical formula for K-alpha x-rays when adapted to the Bohr model becomes

The implication of this relationship is that the single electron in the K-shell before the emission is almost 100% effective in shielding the nucleus so that the electron from the L-shell sees an effective nuclear charge of Z-1. We can use this relationship to calculate approximate quantum energies and wavelengths for K-alpha x-rays.

For example, this calculation for Z=42 gives a wavelength of 0.0722 nm for the molybdenum K-alpha x-ray whereas the measured value is 0.0707 nm. So the agreement is reasonable for K-alpha x-rays even though the upper level of the transition experiences some shielding which is unaccounted for in this model.

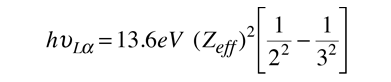

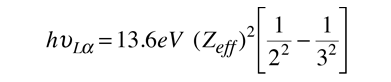

For transitions ending in higher shells, the shielding situation becomes much more complex. From the Bohr model, we might write an equation for an L-alpha x-ray as

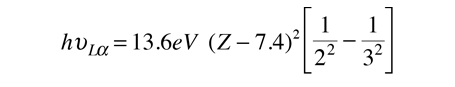

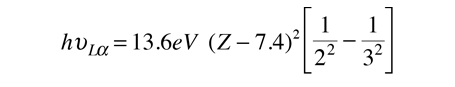

Moseley found that his data for the L-alpha x-rays fit the empirical relationship

so that the best fit to the data was with Z-7.4, indicating a shielding corresponding to 7.4 electrons on the average inside the M-shell from which the electron originated.

|