Mirages

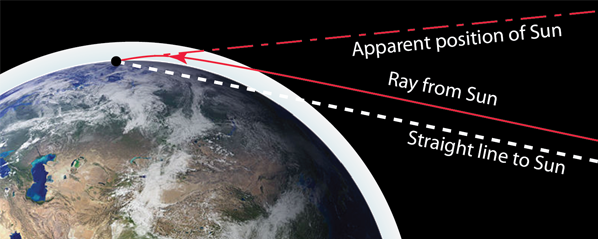

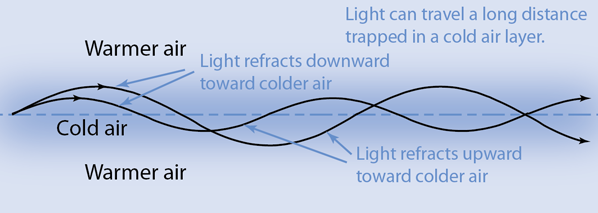

Mirages are produced by atmospheric refraction and are mainly seen in settings where there are large variations in the air temperature, such as in deserts or over cold bodies of water. The refraction which occurs near the Earth's surface is mainly due to temperature gradients where the light rays will be bent toward the cooler side of a given interface.

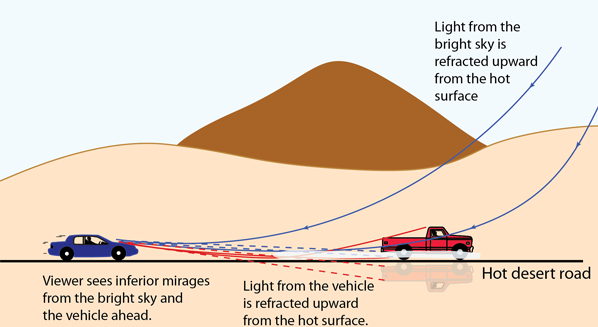

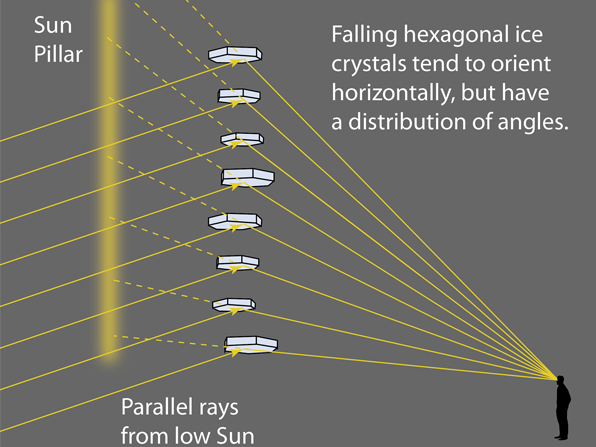

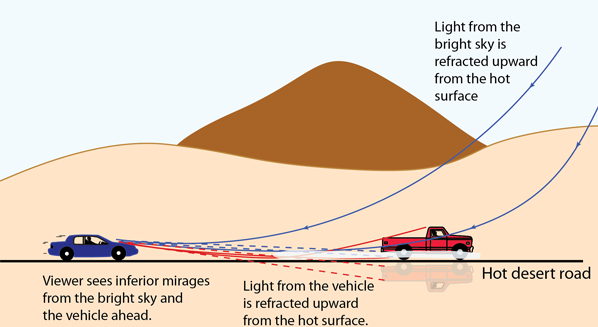

The photograph above was taken on a hot Arizona highway in summer. Refraction bends the light rays from the bright sky upward from the hot surface producing a mirage which has the appearance of a wet surface. Gallant refers to this kind of mirage as a "puddle mirage". The light from the vehicles ahead which moves toward the hot surface is refracted back upward, producing mirage images below the vehicles.

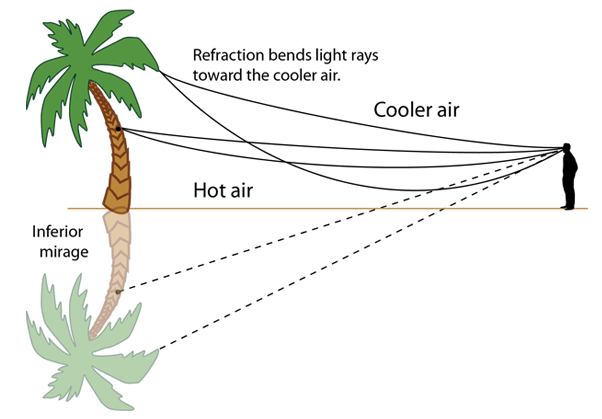

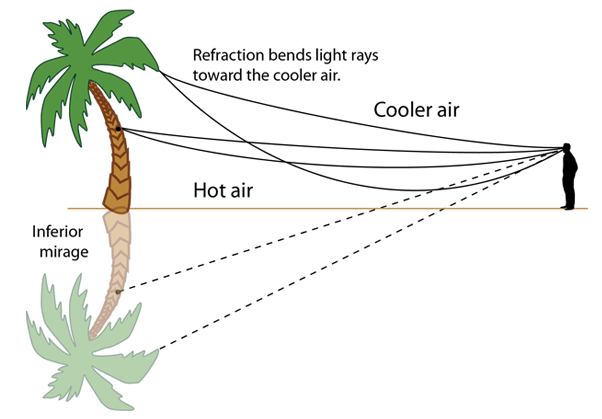

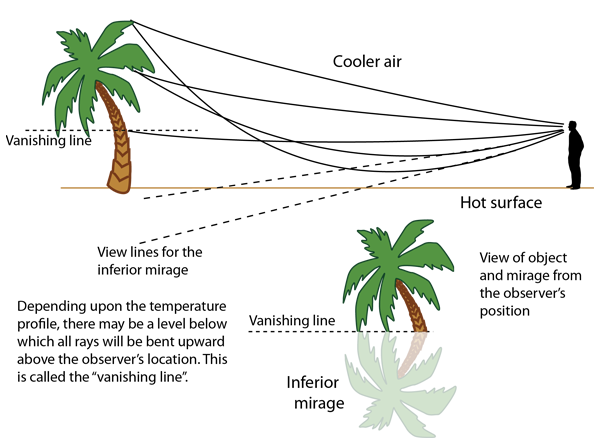

The inferior mirage is produced when light rays from an object approach a hotter region and are refracted away from the hot area. In the desert mirage, the rays approaching the hot surface are turned upward away from the surface. If those upward rays are intercepted by your eye, you see the mirage image appearing below the actual object. Following the pattern of Greenler to demonstrate this kind of mirage, the amounts of curvature shown in the illustration are greatly exaggerated. Such inferior mirages are typically seen from a large distance and the curvatures are much less that those illustrated.

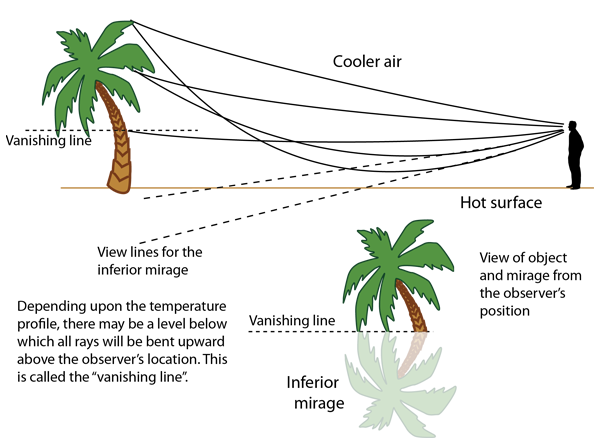

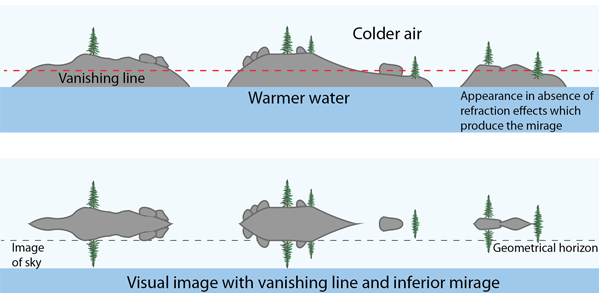

The Vanishing Line

Considering the desert example, the rays from an object will be refracted upward toward the cooler air region. There can be a level on the object such that all rays from points below that level will be refracted over the observer's position. Points below that "vanishing line" on the object will not be seen by the observer. The observer can see both the object above the vanishing line, and corresponding points in the inferior mirage below that level.

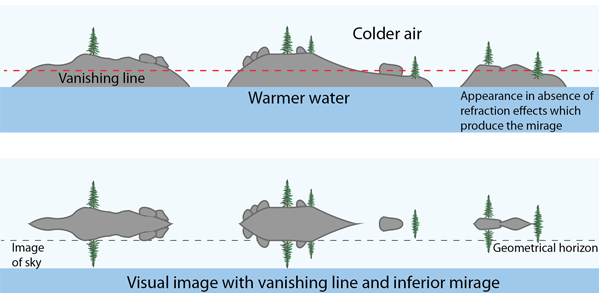

The above illustration is patterned after one in Greenler, based on his observations of lakes in northern latitudes. The vanishing line limits the amount of the distant shore line that is visible, and an inferior mirage is exhibited below the vanishing line. The above illustration shows the inferior mirage at the same vertical scale as the object, but that is not necessarily the case. Greenler notes that the inferior mirage is often vertically compressed. With a greater viewing distance, the vanishing line will rise so that less of the object is seen. Greenler notes that with a small change in viewing height, like stooping down, a dramatic change in the vanishing line may occur. Thanks to Travis Finley for photography and discussion of mirages and the nature of mirages of the sky.

Some aspects of the above graphic are hypothetical - that is, I have never seen one like it. But the link above to Atmospheric Optics shows that the refracted light from the sky does refract to make the mirage, replacing the view of the water below the geometrical horizon. As depicted above, the refracted light from the sky matches in brightness and hue the direct light from the sky, which seems unlikely. I would expect a discernable border between the direct view of the sky and the refracted light from the sky. The extent of the mirage of the sky is placed at the extent of the trees in the mirage of the islands, but that extent would presumably depend on the temperature profile of air around the islands.

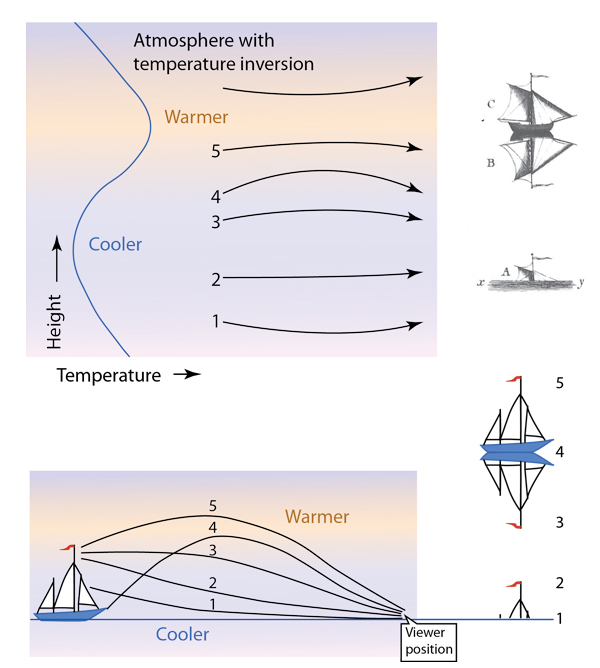

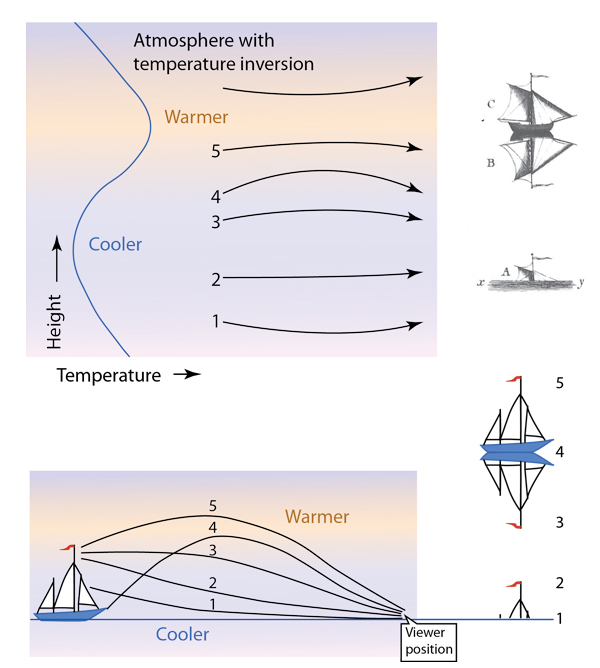

While it is difficult to anticipate the detailed appearance of a mirage, it does appear that those details arise from the nature of the profile of air temperature vs height. Again making use of the work of Robert Greenler with his permission, consider the proposed set of light pathways leading to one of the interesting sailing ship images from northern seas.

These remarkable sketches of the mirages associated with sailing ships were published by S. Vince, "Observations on an Unusual Refraction of the Air, with Remarks on the Variation to Which the Lower Parts of the Atmosphere Are Sometimes Subject", Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society of London 89, 436 [1799].

The illustration below, which is redrawn with permission from Greenler, shows how the left hand image above might have been produced by refraction from the vertical variation of the air temperature. An increase in temperature produces a slight decrease in the index of refraction, corresponding to a slight increase in light speed in the air. From a table published by NIST the decrease in the index is from n=1.0002718 at 20°C to 1.000243285 at 50°C. The tiny change in light speed over large distances produces the visible refraction effects.

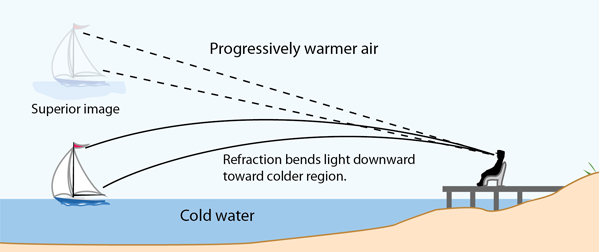

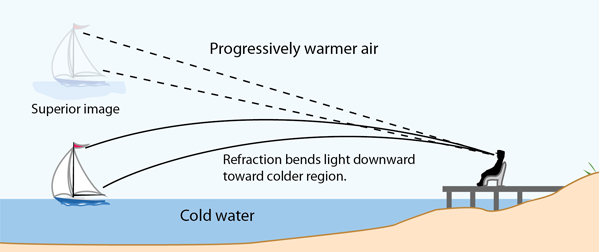

Superior Images and False Horizons

A superior image can be produced when warm air exists over cold water. Again, using the pattern from Greenler, the vertical scale and the curvature are greatly exaggerated to show the effect. Such images are often seen at great distances in the arctic region when the air is significantly warmer than the water. Since the geometry of the mirage images depends on the details of the temperature contour, a great variety of mirage images can be formed.

The superior mirage may appear as an inverted image above the view of the real object. Examples from the Gurney Journey |  |  |

| An image like this ship that appears to be floating in midair, from Explorersweb may not be classified as a mirage, but as a missing horizon. The refraction plus reflection and haze may obscure the view of the horizon, although in this case with close examination you can find the subtle horizon. |

| A YouTube video on boats floating in air and another describing the same phenomenon show examples of false horizons. Such superior images are sometimes referred to as "looming" or as fata morganas. Looming may be distinguished from the missing horizon phenomenon by the fact that the water level rises with the ship. Looming is the phenomenon which can allow you to see a distant ship when it is geometrically below the horizon. |

|