John Grove Speer Journey to California

On p82 of the "Speer Family" book, John Grove Speer wrote:

"The gold fever was now raging and I took it. With father's approbation I set about procuring an outfit to take me to California. A company of eight, consisting of Woodson Oglesby, Jacob Griffith who had been in the Mexican war, William and Christopher Fields, William Souther, John Kalfus, William Russell, of Shelby County, Kentucky, who joined us in Missouri, and myself were formed to make this journey across the rivers, plains, and mountains. Each man had two good mules and four were hitched to each wagon. "

"On May 2, 1850, we went to Louisville and took a steam-boat for St. Louis. At that place we purchased the provisions for our journey, and then took another steamer for Lexington, Missouri, where we began our overland journey for Lone Jack neighborhood in a border county, where we maintained until the grass grew sufficiently high to sustain our animals. At this place we were joined by another company of eight men gotten together by Captain Easley a pioneer settler and hunter. We all started together for the Pacific coast."

This is a steamboat from somewhere around that period of time, gotten from the cover of "Steamboats: Icons of America's Rivers" by Sara Wright. There is information about 1800s steamboats in a Wikipedia article. The casual way in which the steamboats were mentioned suggests that they were well-known ways to travel on the Ohio River down to St. Louis. The implication was that they took their mules and wagons with them on the ships. Neither of these types of ships appears to be particularly suitable for carrying mules and wagons, and I did see some other examples with more open decks. In St. Louis they transferred to another steamboat for the journey up the Missouri River to Lexington, Missouri. |  |

| This paddlesteamer from the Wikipedia article is described as a "typical river paddle steamer from the 1850s", so one of these types of steamers may be the type taken by Speer and his company. The journey to St. Louis was on the Ohio River, and the second journey to Lexington was on the Missouri River. |

Scaling the straight line distance for this first phase of their journey gives me about 430 miles. Road distance is more like 475 miles.

The story takes them from Lexington on the Missouri River to the Lone Jack neighborhood, and Lone Jack is currently a southeast suburb of Kansas City. There was no mention of Kansas City in the narrative. |  |

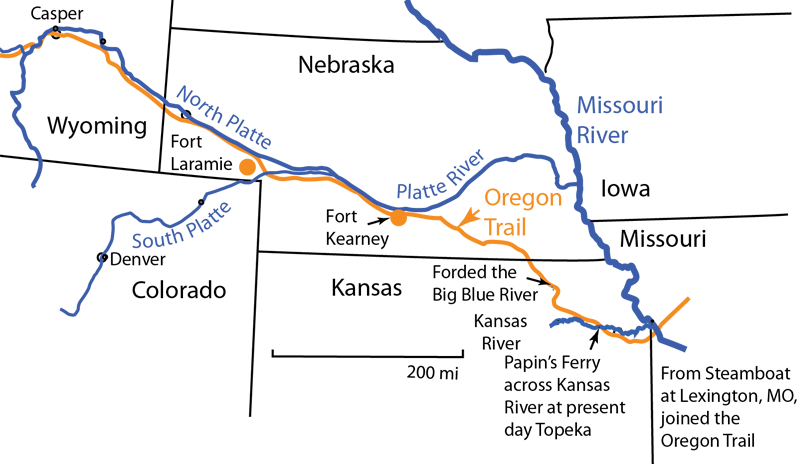

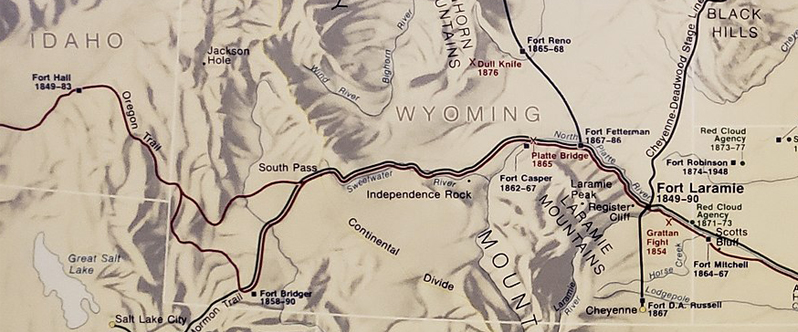

John Grove Speer, p83: "Out on the vast prairie among Indians, over rivers, onward we moved. After having crossed the Blue W___ and Kansas Rivers we were nearing the Platte a distance of about 340 miles, just above Fort Kearney from this point we traveled up on the south side of the Platte to Fort Laramie, then garrisoned by United States troops, where we had some blacksmithing done. The distance was about 640 miles to this fort. Now as you would like to know what was seen and done on this trip, I shall devote part of these pages to telling you. We saw many Indians some tutored and some not, but all looking like savages. We passed through the Potawatomi Mission where they were being schooled. After we passed through the mission we met some of the warriors of this tribe returning from the pursuit of some hostile Indians who had been committing depredations upon some of their tribe. We saw a few buffaloes and antelopes. Captain Easley killed one of the latter and brought it into camp. The meat is very sweet and tender, even better than venison. Antelopes are much like deer, but smaller; the male antelope has no antlers."

|  |

The mention of the Potawatomi Mission where Indians were being schooled indicates that they traveled almost directly westward from Lone Jack. Web says it was Northwest of Topeka. From above linked article: "The Potawatomi Mission near Topeka operated just 13 years, from 1848 to 1861. It suffered from sporadic shortages of funds and staffing throughout its short history, but the outbreak of the Civil War in 1861 made these problems insurmountable. When Kansas became a state that same year, the Potawatomi reservation was reduced dramatically in size, and most of the tribe moved to Indian Territory (present-day Oklahoma)."

Speer mentions crossing the Kansas and the Blue Rivers (also called the Big Blue River), and these two rivers are mentioned in an article on the Oregon-California Trail. That article contains the following: "It is estimated that 300,000 people traveled to the West Coast during the 20 years after the first caravan went to Oregon in 1841. Almost all of these people traveled through northeast Kansas along what became known as the Oregon Trail. This road, also called the Oregon-California Trail, was a 2,000-mile route beginning at Independence, Missouri, and continuing west and north to the Columbia River Valley in Oregon or west then south to the gold fields of California. Kansas was the gathering point for wagon trains. " It also mentions the Potawatomi Mission as one of the popular stopping places.

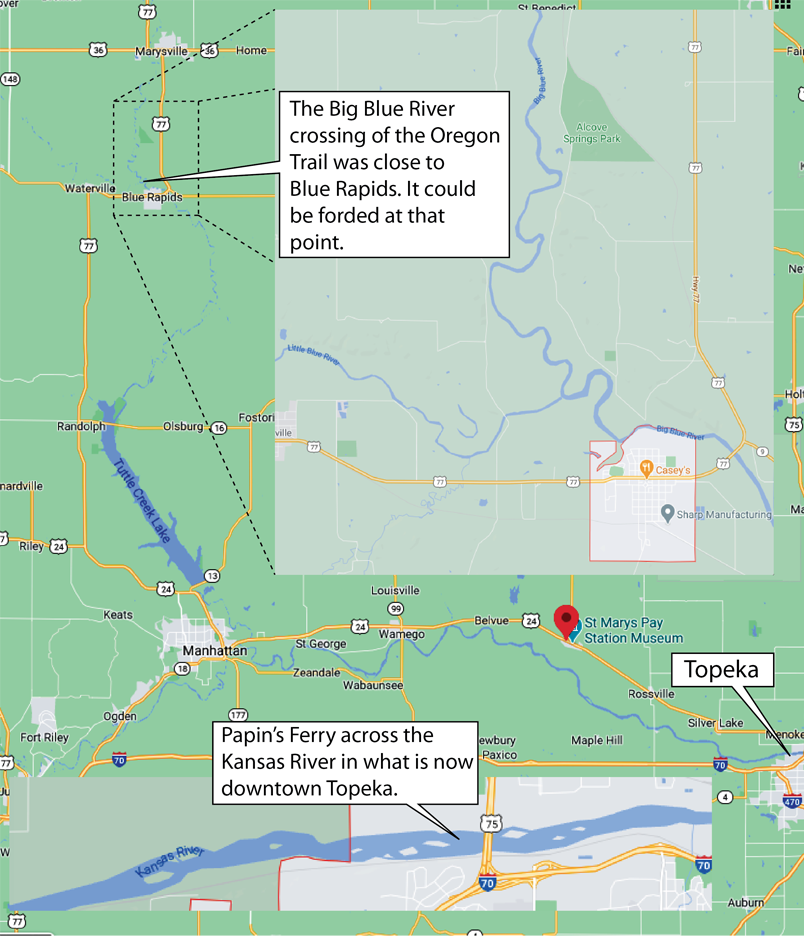

All the comments that I find indicate that they were following the Oregon Trail at this point in their journey. The route to California branched off southward west of this point. The referenced article above says that they had to use a ferry to cross the Kansas River, a large river.

| Oregon Trail crossing on Kansas River View of the Oregon Trail crossing near old Uniontown in western Shawnee County, Kansas. This crossing site was considered the last point west of the Mississippi River where supplies could be purchased en route to Oregon. |

Speer's casual comment "After having crossed the Blue W___ and Kansas Rivers ..." covers what had to be quite an adventure. When they traveled westward from Lone Jack, they had to turn north on the Oregon Trail and then they faced the Kansas River, which was described as "wide, deep, and swift", so there was no way they could cross it with wagons alone. It is likely that they crossed on Papin's Ferry, as most travelers on the Oregon Trail did. You could say that they crossed the river in Topeka, but Papin's Ferry preceded Topeka! I found one record that said that Topeka had five houses in 1855, so Topeka was in the future, built along the Oregon Trail at that location. Then they traveled northwest to the point where the much smaller Big Blue River could be forded, still following the Oregon Trail. It was the travel from Papin's Ferry to this ford point that took them by the Potawatomi Mission. The straight line distance between the two crossing points was about 60 miles.

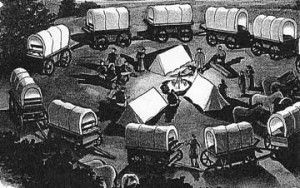

| Past the crossing of the Big Blue River, the Oregon Trail continues northward into Nebraska and westward across southern Nebraska to Wyoming, part of it along the Platte River. This was a long stretch for the 16 men, and I'm guessing 8 wagons since it was commented that each man had two mules and four mules to each wagon. There were some classic pictures along the way, like the circling of the wagons at night. |

p 83: After a day's travel we would put our wagons in a circle, picket our mules by tying them to a stake driven into the ground with a lariat, or rope, about thirty feet in length, thus allowing them to graze on a circle sixty feet in diameter, our tents were then put up and two guards selected to watch our mules, one in the first part, the other in the latter part of the night. One night while I was on guard the mules were very much frightened, probably by some wild animal that was prowling about. I ran to the point where the mules had broken loose and fired into the darkness with no effect, save to arouse my companions who quickly secured our frightened mules.

p84: "The next scene worthy of mention was high up on the Platte River, where we got among the buffaloes crossing the stream.

Several of them were killed by members of our party. I shot an old buffalo in the head with my fine old rifle (fathers target gun). I cut some of the steak from the carcass and took it t our wagon; it was coarse and dark and was not good like the sucking calf that was killed and brought in by Captain Easley. I need not tell you of the little and big jackrabbits and the sage hens that we saw.

Thousands had crossed and the foot-hills as far as the eyes could see, were covered with them.

The latter live upon the seed of the wild sage brush that grows very abundantly, and is so firmly rooted in the ground that we often tied our mules to it. One evening we had two rabbits and a sage hen to be cooked for our supper. Woodson Oglesby, one of the very nicest men in our company made up the dough for bread and rolled out some very thin to drop in, that we might have an extra dish, but lo and behold! that sage hen spoiled the whole mess, and destroyed our fondest hopes. It was so bitter and strong of sage no one could eat it. The sage hen is of the color of sage leaves and about the size of a guinea hen. "

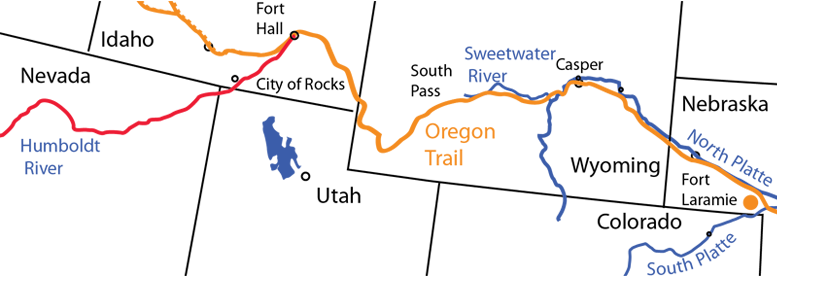

| Still high up on the Platte we traveled passing the forks, then up the south fork until we reached the place where the great emigrant trail crosses it, when we sent two of our company across to ascertain its depth and show us where to come out on the opposite side. One returned to pilot us over. We had to raise our wagon beds as high up as we could and fasten them to the standards to save our provisions from damage. I think this stream at this crossing is from one to two miles wide and has a floating, quick-sand bottom. I drove our four mule team across, and I had to keep them moving briskly to keep them from sinking. (He says "up the south fork", but it appears that he means "up the south side of the north fork" because the next location is on the Sweetwater.) |

This illustration of the crossing of the Platte River is from the R. Atkinson Fox Society website. There is much literature on the web about the Platte River and the Oregon Trail in general. After the crossing of the North Platte River, they traveled along the Sweetwater River. |  |

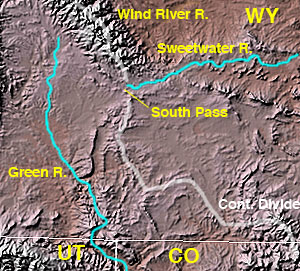

Again we moved on crossing another stream called Sweetwater , the water of which was said to be poisonous. [Current articles like the Emigrant Trail in Wyoming do not mention that the river was poisonous, but they mention some alkaline springs near the river, which would be poisonous to their animals.]

- Three crossings on the Sweetwater River.

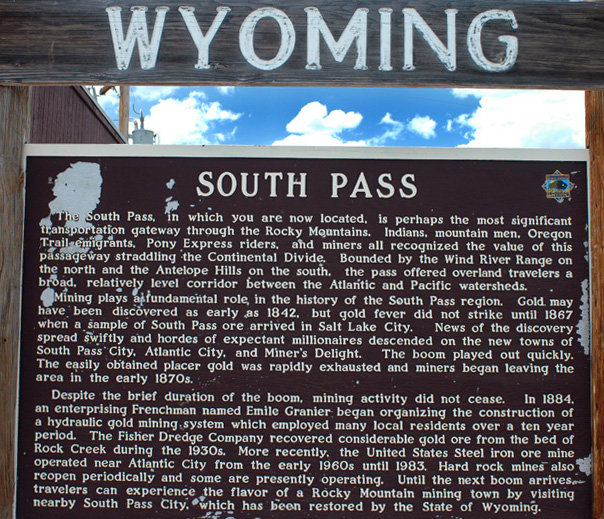

Wikipedia | On and up an almost imperceptible grade we went until we reached the south pass of the Rocky Mountains. A day or two before we reached the summit, we traveled over the best gravel road I ever saw, more solid than any turnpike over which I ever traveled. While on this great elevation, we saw a heavy, dark cloud drifting towards us, while the sun was seen shining on the top of it, which seemed to be smooth and level, while underneath, it looked dark, ragged and threatening. When near the mountain the wind struck it and carried it south after having poured out a heavy shower that made the road quite wet a short distance ahead. So I was once above the clouds, for in descending from the summit we go down a steep, high mountain into a valley, or low plain really lower than the last ascent. |

This photo of the South Pass along the Oregon Trail is from the Wikipedia article. |  |

| The 1812 discovery of the South Pass by European Americans, as a natural crossing point of the Rockies was a significant, but surprisingly difficult achievement in the westward expansion of the United States. Because the Lewis and Clark Expedition was searching for a water route across the Continental Divide, it did not learn of South Pass from any Native Americans in the area. Instead, the expedition followed a northerly route up the Missouri River, crossing the Rockies over difficult passes in the Bitterroot Range in Montana. Wikipedia |

In 1811, the overland party of John Astor's Pacific Fur Company, although numbering sixty well armed men, found the Indians so very troublesome in the country of the Yellowstone River, that the party of seven persons who left Astoria toward the end of June, 1812, considering it dangerous to pass again by the route of 1811, turned toward the southeast as soon as they had crossed the main chain of the Rocky Mountains, and, after several days' journey, came through the celebrated 'South Pass' in the month of November, 1812.

| The night after our safe descent, we were treated to a surprise, for next morning there were several inches of snow on the ground. For once we did not remain to breakfast on the spot where we spent the night, but were up and off in double quick time, until we could find grass for our mules. Before we got out of the snow, we saw where a bear had crossed the trail, making its way to a small grove of timber on our left. Just at this time an old mountaineer, who was on the bear's trail, came up and said he thought he would get it in that little grove. |

| p86-87: "The warm sunshine soon melted the snow and we found grass for our stock, halted, cooked and ate a meal and were soon on the road again. On and on we moved, now to see large ledges, yes, acres of naked rock on right and left scattered about over the plains. This is the favorite home of the wild mountain goat which we have seen but never have been able to capture any of them. They are crafty and hard to capture. If you get after one, it will strike out for one of these rocky fields , and right over it he will go jumping from rock to rock without making a false leap and down on the other side, then away to another rock before the man can ride around to get a shot at him.  |

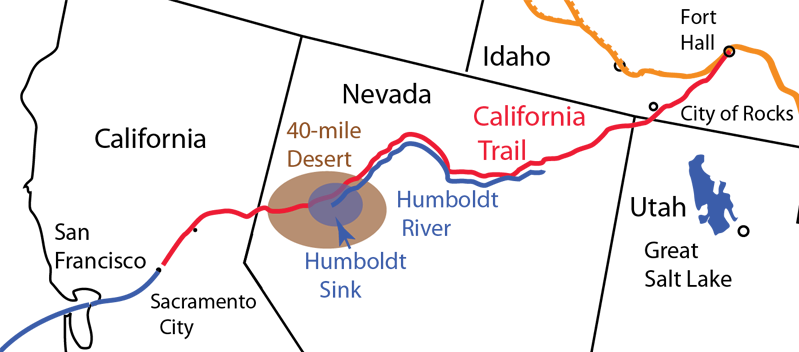

"We have seen no Indians since we left the Platte, but as we went on westward we came to a camp of the redmen, their squaws and little ones at the bend of Bear River. They had come down from the head waters of the Columbia River on a hunting expedition. The were of Flathead tribe. I suppose most of the men were out on a hunt, for though we stayed there several days we saw but few of them. There were a white man, his wife and a Cherokee Indian with them, with whom one of our company traded and got a good American horse that carried him into Sacramento City, where he sold him for about ninety dollars. Now, having a chest of medicine with me which I desired to take to the end of the journey, I was surprised and troubled to learn that here we would leave our wagons and make the remainder of the trip on pack mule. I scarcely knew what to do, but decided finally that I would not cut up our wagon, but get ready to, and go as a majority favored so doing. Fortunately Captain Miles, of Missouri, who had been out in California in 1849, came up with his ox team on his return trip, and to him the wagon was given. He agreed to bring my chest of medicine on to California, which he did like a good man. I lost all in a fire in Nevada where I had left it with a friend of mine, and by that means lost almost one hundred dollars worth of medicine."

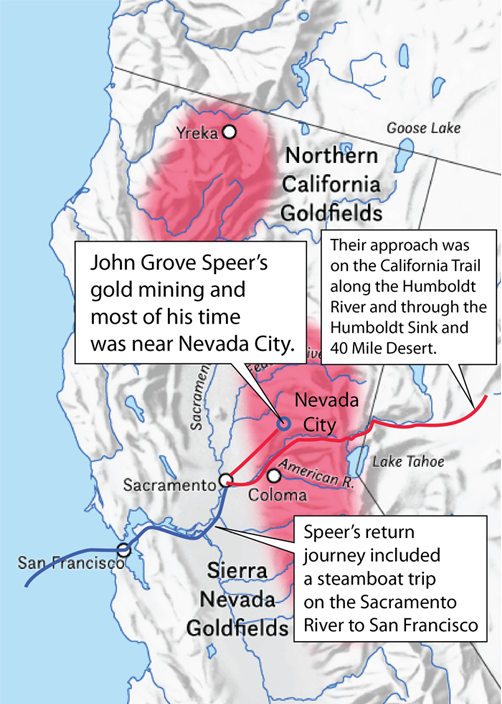

p87-89: "Further on we reached what was called Hodgpeth's cut-off which caused us to leave Salt Lake City about seventy miles to our left as we journeyed on to the head of Humboldt River which is about three hundred and forty miles in length when it sinks or comes to an end in the great basin east of the Sierra Nevada Mountains. Our route was down the north side until we reached the sink, when, having supplied ourselves with fresh water, we struck out to cross a parched desert where there was no fresh water to be had for a distance of about ninety miles. After our evening meal we took the trail for the Carson River where we found a plentiful supply of fresh water. The sand was do deep for a part of the way that one of my mules, that had been poisoned by drinking alkaline water gave out. I gave him something to eat and left him behind. I was sorry to do so , but all was rushing at break-neck speed and I was compelled to do do or be left by myself. There is not a tree of any size growing on the Humboldt River as it rolls on draining a great basin and gathering in volume until near the end where its surface is covered with thousands of whirlpools which seem to suck in the water. What becomes of this water is a mystery. There is one thing that is significant and that is that near the sink there is a volume of water issuing from the ground that is hot enough to cook an egg. It ebbs and flows as the ocean tides, I am told. This water I think is fresh and can be used for culinary purposes, but all the water down here where the river is from one to two miles width and very salty."

|

|

This is a Google Earth view of the Humboldt Sink. It is interesting that there is some irrigated cultivation in the area. It is also interesting that that Interstate 80 and a railroad runs through the area that caused so much grief and distress to those early travelers. An article for farmers in the Nevada News Group shows that the water issues and the nature of the area have changed dramatically since the gold-rush days.

This is an image of the Humboldt Sink from Wikipedia titled "Panorama of the Humboldt Sink from the West Humboldt Range in Churchill County, Nevada"

"On we go towards the Sierra Nevada Mountains and at length begin their ascent. After climbing two or three miles we are on their summit far above the tops of the pine trees which are to be seen everywhere on these mountains. The north sides of these mounts are covered with snow all the year , and on the slopes one can enjoy scenery that is grand and magnificent. This is the highest place I was ever on out there, and was several hundred miles from Sacramento City with pine forest all he way. Here we took a pack trail and passed a beautiful lake of clear water about five miles in length situated upon this high tableland. Where we came to where its waters fell over a precipice and dashed down through and among the rocks an on to feed the larger streams. We crossed here on a pontoon bridge that had ben placed there by packers, the span was about thirty feet, and the water above about ten feet deep and so clear that we could see many mountain trout on tis bottom. "

p89: "As a company, our last camp was on the American River which empties into the Sacramento River at Sacramento City. At the ferry of the American River we cooked and ate our last meal, and then the separation took place. Several went into the city, and some of them falling in with Richard J. Oglesby, a forty-niner, concluded to go south with him where he was mining, and the next morning moved off, with their mules to be placed on a ranch. The others left, two by two, leaving me and Joe Griffith, who had joined us on the plains, to shift the best we could. I had gone into the city that night also, and was called upon to make a speech to a crowd who wanted to know the the suffering and the destitution of the emigrants, that they might send out relief parties with provisions, etc., to meet them. Of course I told them what I knew."

p89-90: "The next morning, Joe Griffith and I cleaned the platter, and mounting our animals rode into town and offered them for sale. We then secured a meal of good things and were ready for some other move. "

| "There were no gold mines near Sacramento City, and we did not know in what direction to strike out, but providentially, as we were walking down the street we met a man carrying a wagon whip in his hand. I knew him, hailed him, and took him by the hand, but he did not know who I was until I told him. He was James Taylor, of Decatur, Illinois, and a partner of Esq. Henry Prather and he was down hauling provisions up to Nevada City where they were sold by Mr. Prather, an acquaintance and friend of mine. We were informed of the rich gold mines up there and soon made ready to accompany him a distance of eighty miles to Nevada City at the forks of Deer Creek in Nevada City, where already several thousand men were at work taking out the yellow metal. It took us two days to make the trip. One morning before we left camp a large, almost nude Digger Indian strolled up and looked into our wagon, but soon struck out again over the hills. After a little prospecting for gold, we bought a claim up on Deer Creek for which we paid two hundred dollars. Providing food, we went to work in earnest and averaged about eight dollars a day as long as our claim lasted. The only sickness that I had while in California was while working in these diggings. I laid by at Mr. Prather's store where he was very kind to me, and in a week or two was well again and throwing the sand and gravel out of the way to get at pay dirt. One of our party who had so unceremoniously left us at Sacramento came begging us to take him in as a partner, saying he was out of funds and would have starved had he not fallen in with a generous hearted German. We let him have an interest in the claim. |

Reference: This material attempts to trace the journey based on the text of the book "Reminiscenses of the Speer Family" written by John Grove Speer when he was 91 and published in 1900.

| Miner, Postmaster, Doctor, Sailor |

| John Grove Speer 1890 |

1800's